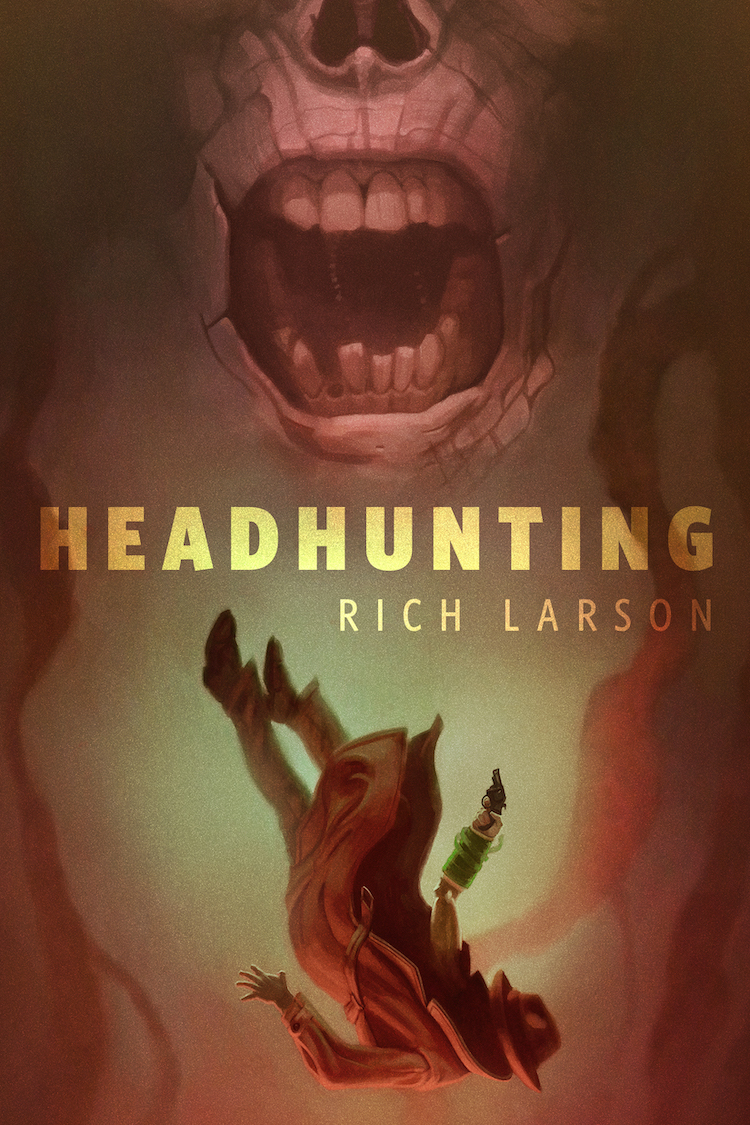

A private eye plagued by hallucinations is hired to retrieve a mummified monk’s head stolen from a cathedral–but why would someone want it?

Amir wakes up from a dream about a flesh-and-bone piano, and when he gropes his phone out from under his pillow he sees three missed calls. Bravetti never puts anything in text, or even encrypted text, but they’re not together anymore, or even drunk-dialling, so it must be a job. He thumbs the call icon, then the speaker icon, then lurches out of bed.

He takes a small metal pot from the stovepad, adds a splash from the tap. Returns it and sets it on high. He holds the coffee jar against his ribs and uses his left hand to wrestle it open, since his right is encased in lime green fibreglass, then rewards himself with a slug of codeine from the little brown bottle that came with the cast.

Bravetti answers before the water starts boiling. “Have a nice lie-in, did you?” she asks, that cool, dry voice you could store perishables in. “Three bleeding times I called you.”

Amir heaps cheap focafe into a bone-white mug. “Saw.”

“Got an easy one, but I’m out of town—” She breaks off, and Amir thinks he can hear the metallic rush and creak of a train. “So I’m passing the savings on to you, mate. Can you work?”

Amir observes the steam from the pot, the first few tentative bubbles. He runs a fingernail against his waffled cast. “Will I need two hands?”

“Will you need two hands?” she echoes. “What the fuck sort of question is that, Amir? Have you lost one? Is everyone just up and misplacing body parts this morning?”

He waits.

“But no,” Bravetti says. “This, you could probably sort out with your little finger. You know St. Johan’s Cathedral? The one with the mummified crusaders?”

The little slice of water is boiling at last. He dumps it into his mug and stirs until the grey granules of focafe are fully dissolved. “Yeah,” he says. “Went there on a school trip as a kid.”

“So did I. Everyone ought to. Bloody fascinating stuff.” She moves past someone else’s muffled conversation. “Anyways, they were burgled.”

“And didn’t call the coppers?”

“Obviously not, if they called me.” Amir hears a sliding door, which cuts the background noise, then a rustle of fabric. A liquid trickle. “They know who did it, see. Cams caught him clear as day. It was the director’s own nephew, so they just want the item retrieved, is all. No coppers. No chatter.”

Amir sniffs at the focafe; it smells awful but part of his headache is already peeling away in anticipation of the caffeine. “What’s the item?”

“One mummified head,” Bravetti says, sounding almost gleeful. “One mummified fucking head.”

Amir sips from the mug. “Are you taking a piss?” he asks.

“Not at all,” Bravetti says. “The director’s nephew nicked a head from one of those mad crusader monks, and you’re retrieving it before he sells it on the darkmarket, or makes a bong of it, or something.”

Because the focafe cannot possibly taste worse, Amir glugs a bit of codeine inside and gives it a scraping stir. “I said a piss,” he says. “I mean right now. As we speak. Are you on a train, in the lavatory, taking a piss?”

“No. Of course not. That’d be disrespectful.” Bravetti’s voice carries a hint of genuine annoyance for the first time. “You want the job or not?”

Amir looks around his new flat, a white prefab box that’s unfurnished apart from his gelbed and a small rickety table stacked with books, a bit of rumpled cash, and a handgun. He looks down into his one and only mug, which now contains a witch’s brew of fake coffee and hospital drugs.

“I want it,” he says, sitting down on the edge of his bed. He takes another noxious sip.

“Grand,” Bravetti says. “I’ll send the director your info and rate.” She pauses. “You’ve been feeling better, yeah? No more, ah, episodes?”

“Loads,” Amir says, resting his cast on his knee bone. “Loads better, I mean.”

“Grand. Then I’ll—” Amir hears the sound of an automated toilet flushing. “Ah, fuck,” Bravetti says, and hangs up.

Amir finally disembowels his duffel bag, dumping its contents across the bed, and tries to divine the least wrinkled shirt and trousers. The director wants to meet in person in a nearby plaza, which speaks to a certain paranoia common among those taking their first wobbly steps into legally grey areas.

Amir used to try putting such clients at ease. He would practice making his eyes warm in the mirror, making his nods weighty. Of course you’d never normally do something like this. Of course you deserve to know what they’re up to. Of course they need to be taught a lesson.

He used to put so much care into his craft, but when he stopped he discovered it didn’t matter. Some clients even seemed to prefer speaking to a frosty-eyed thug. Found it comforting, maybe, to be the only real human in the interaction.

There is no way to make a lime-green fibreglass cast look professional—he’d chosen the neon hue whilst shithoused—and his shirt sleeve doesn’t fit overtop. He tucks the loose fabric into the sweaty crack, then hides the whole business in his raincoat. Once he shaves his face and spoons his feet into boots, he’s ready to go.

“Nice to know I’m not the only one losing their head,” he tells the mirror. “Maybe we’ll bond over that.”

“Loads better?” his reflection says, raising both bristly eyebrows. “No more episodes? You’re such a bad liar, mate.”

Amir pushes out into the unfinished hallway, where a row of neatly painted black doors floats in bare concrete and electric veinery. He checks the caked construction dust for tracks, specifically the sort left by flippers, but finds none.

There’s a shambles set up between Strand Street and Hatter’s Bridge, its silhouette razorous, insectile. Amir can see pale, doughy bodies moving along the rusty conveyors. From a distance they almost look like maggots, but when they’re slit and drained the torrent is bright red, mammalian blood. Rubber-suited priests slide about on the gore-slick cobblestones.

Amir feels almost certain that mechanised human sacrifice in the Old Town is not a regular occurrence. He shuts his eyes tight, presses the heels of his hands to the sockets. Focuses on the bruise-coloured dark. He counts to three before he opens his eyes, but the shambles is still there, converting citizens to sundered meat, churning out feed for some long-lost god. The whole scene is wreathed in body-heat steam.

“Hello?” The voice is quavery, timid. “Are you the one who finds things?”

Amir drags his gaze away from the butchery, and sees his client has joined him on the stone bench. The director is small and immaculate, wearing titanium-framed smartglasses and a black coat and an elaborate purple scarf. He’s sweating despite the winter air; the perspiration gleams on his shaved scalp like baptismal oil.

“That’s me, yeah,” Amir says. “You the one who loses them?”

The director grimaces. “I didn’t lose it,” he says, confirming he’s not the humorous sort. “It was stolen. By a rash, foolish young man. Who also happens to be a family member.”

Amir feels a poke at his hip bone, and realises the director is trying to very stealthily pass him a nanodrive. He has to reach across himself with his left hand to take it, which earns his concealed right arm a suspicious look.

“Why are you doing it like that?” the director asks. “That makes it obvious.”

“I’m left-handed.”

Amir wriggles his phone out of his pocket, then pins it to his knee while he works the fingernail-size nanodrive into its port. A plex of photos, all depicting a rangy nineteen-year-old with curly black hair and an inchoate moustache, appears on the screen. The tags identify him as Lester Bowright.

“The theft occurred last night,” the director says. “I discovered it early this morning, and after I watched the security footage—that’s on there, too—I tried, of course, to track him down. But he’s not answering my calls, and his flatmate claims he never came home.”

“Any bars or pubs he particularly likes?” Amir asks. “Might have taken it out for a drink. Wanted to show it off to the lads.”

The director recoils, makes a noise like a cat hacking up hairball. “No!” he exclaims. “No, no, Lester wouldn’t do that. He’s a bright boy. Very solemn. Very studious.” He uses the edge of his scarf to wick sweat from his forehead. “Which is what makes the theft so baffling.”

“Money troubles,” Amir suggests next, recalling Bravetti’s theory. “Needed some quick quid. There’s a market for this sort of thing, yeah? Pilfered artefacts?”

“I suppose.” The director looks pained. “I suppose some unscrupulous private collector—I mean, the Three Mad Monks are legendary.”

“There’s an ale named after them,” Amir says, with a weighty nod. “Could be he took it straight to the buyer’s people, in which case the mummified head’s out of the country already.”

The director makes his sick cat sound again.

“Or he could be holed up somewhere,” Amir adds, “waiting for the buyer’s people to come to him. In which case, for the agreed upon fee, I’ll do my best to find him and retrieve the mummified head before it’s out of reach.”

“Oh god,” the director says, staring off into the distance. “Oh god, what a mess.”

Amir follows his sightline and feels a hot flicker of hope. “You see it?” he asks. “What they’ve set up there by Hatter’s Bridge?”

The director frowns. “What?”

“The shambles,” Amir says, even as the hope cools to slippery lard in his belly. “The sacrificing.”

“Always under construction, that bridge,” the director mutters. “Always a proper shambles.” His eyes jig behind his smartglasses; a bank transfer slides onto the screen of Amir’s phone. “There. There’s your deposit. Now please, go find my head.”

Amir starts with Lester’s flat, taking the metro north and disembarking at Our Lady of the Tar-Black Snow. He ascends the concrete stairs, winds his way through the filthy station, and re-emerges into a cold grey afternoon. His right hand is aching inside its fibreglass, but he forgot the codeine bottle at home so there’s nothing for it.

He passes the church and its cadre of squat geometric angels. There are no eyes in their smooth stone faces, but they seem very vigilant all the same, perhaps having heard St. Johan’s was burgled. He checks the address on his phone again, then hooks down a ruelle that leads to a row of old houses now converted to apartments.

He lopes up to the specified door and buzzes number 212. For a moment, nothing. A grimy pigeon flutters onto and then off the stoop. An ambulance banshees past in the distance. Then a static-flayed voice answers.

“Hello? Who is it?”

“Hello,” Amir says. “Amir Murtle, PI investigating the disappearance of one Lester Bowright and a linked theft. His uncle may have told you I’d be coming through.”

“Right. Fine. Up the stairs, end of the hall.”

The door clacks and buzzes; Amir yanks it open left-handed. He steps into halogen lighting, black-and-white carpeting, walls marked up from a hundred hasty moves. It smells good, at least. Hash hanging in the air, a spicy cooking scent wafting from up the stairs. He follows the latter, then reluctantly passes it by in favour of door 212. Lester’s flatmate is waiting.

“As if that’s your real name,” she says, kicking her door all the way open with one thickly socked foot. “Amir Murtle.”

She has glowing blue teeth implants and interesting tattoos, plus a canister of mace dangling oh-so-subtly from the bridge of her folded arms. Amir sheds his raincoat, exposing the lime-green cast that will make him look less professional, but also less intimidating.

“It’s my real first name,” he says. “Murtle’s made up, yeah.”

“What’d you do to your arm?”

“Fought an animatronic walrus.”

She narrows her eyes. “If you want me to answer a bunch of questions honestly, you really ought to set a better example.”

“I smashed it with a hammer,” Amir says. “To score painkillers.”

She snorts, but lets him inside. The flat is bursting with vegetation, pots on every spare surface and hanging planters in the corners, one of which is being watered by what looks like a scrapped-together DIY drone. There’s a vaguely familiar print by some famous Taiwanese artist on the wall, all fiery orange and sea blue. Charcoal sketches are tacked up around it.

“This lot’s all me,” she says. “Before you start psychoanalysing too much. Lester mostly keeps in there.” She points to a featureless white door. “Normally he gets home at six, says hello, cooks himself something, and heads to his room. Rarely emerges. Gets up before me in the mornings. It’s really a terrific symbiosis.”

“Last night, though?”

“Just never came home,” she says. “I was quite happy for him until his boss from the gallery came around. Boss-slash-uncle, I guess.” She looks at the door and gives a shrug. “Thought he was finally shagging someone.”

Amir crosses to the door, tries the handle. “Not a lot of friends over, then?”

“Never.”

“Any odd behaviour in the past week or so?” Amir asks by reflex, focused on the lock. “Any signs of stress?”

She scowls. “I’m not his therapist, am I?”

“Your name?”

“Fay.” She pauses. “Koffyew. Tosser.” She nods. “Fay Koffyew-Tosser. Hyphenated surname.”

“Hard to do it on the spot,” Amir says. “Fay, though?”

“Fay, yeah.”

Amir gets out his picks. “Fay, I’m going to pop this door open and have a gander,” he says. “Won’t be more than ten minutes.” He inspects the stiff fingers of his right hand, curls them as far as he can. “Maybe twelve. After which I’ll leave everything in its place.”

“Seems a bit illegal,” Fay says, folding her arms again.

“You can look elsewhere, if you like,” Amir says, groping around in the bottom of his pocket. “Maybe into the soulful eyes of—” He peers at the rumpled note. “Whoever’s on the fifty.”

“Now it seems even more illegal,” Fay says, but she’s become a sapient storm cloud, a dense ball of dark grey vapour illuminated by flashes of sheet lightning, and Amir does not negotiate with hallucinations. He tosses the note in her general direction, as he’s no longer sure where her hands are, then sits down to pick the lock.

Fay only rains on him for a few minutes before she drifts away, and a few minutes after that he’s in. Not many tactile sensations compare to successfully picking a lock—mucking out a waxy earhole with a Q-tip might be closest—so Amir takes a moment to relish the scrape and click and clunk.

Then he turns the handle and steps into Lester’s room. It’s disturbingly familiar: gelbed in the corner, cheap spindly table, bare walls. Lester does not have much of a nesting instinct, but that makes for a quick search. Amir’s already onto the closet when Fay pokes her restored head in.

“Oh,” she says, through a mouthful of falafel. “Anticlimactic.”

“Sorry,” Amir says, turning out the pockets of a wrinkly blue blazer.

“What did he steal, then?” she asks, dabbing yoghurt sauce off her plastic plate. “He never seemed like the stealing sort.”

Amir replaces a metro stub and wadded tissue, sets the blazer back on its hanger. “What sort did he seem like?”

“Bit of an ascetic, I guess.” Fay rubs crumbs off her fingers. “Always eats the same things. Wears the same clothes. No boozing, no vaping. No pills when I offered.”

Amir lifts up a Crystal Palace hoodie pooled on the bottom of the closet and finds a pair of cracked smartglasses underneath. They’re long dead, but when he hooks them to his phone the charge light still comes on—potential jackpot. He discards the hoodie, waits for the red sliver of battery to struggle upwards.

“You need anything?” Fay asks. “Because I could get you painkillers, easy. No bone-smashing required.”

The glasses turn on, and Amir holds them up to his face. Notifications split and refract along the cracks. Lester’s still logged in, but the glasses haven’t been used in months. Amir syncs them to the homenet, and suddenly Lester’s featureless white room transforms into a teeming mass of text and photo.

Some sort of excavation, archeologists working in grainy black and white. A diagram showing the measurements of three stone sarcophagi. Colour close-ups of a sunken brown face, skin shrivelled, eyeless but not entirely lipless—Amir can imagine the exact texture of that mouth, and it makes him feel slightly nauseous.

The theme’s pretty clear, even before he starts skimming the wiki articles. Third Crusade, Three Mad Monks, St. Johan’s catacombs, parasitism. The last one’s a bit odd, but not nearly as odd as the finger-scrawled message superimposed all over the place. The shaky lettering is different on each, not copy-pasted, which means Lester must have carved it into the air a hundred different times.

Death is a membrane.

He checks the lower left corner of the glasses and sees Lester’s account is active in two locations: here, and somewhere in the Tannery District.

He gets Fay to wear the glasses as well, just to verify, and takes her number in case he needs more information or cheaper opioids. Then he heads for the metro again, dialling his client on the way. The director picks up on the third ring.

“Yes?” he whispers. “Have you found it?”

“Nearly,” Amir says, passing the faceless, birdshit-spackled angels. “Lester’s been taking his work home. Even before the head, I mean. When did he start working the exhibit?”

“Three months ago? I’d have to—have to check.” The director pauses. “Taking his work home in what sense?”

Amir looks at the access times on the images, the articles. “He got obsessed with those monks about a month in,” he says. “He may have been planning this for quite a while.”

The director gives a soft groan.

“Death is a membrane,” Amir quotes, pausing at the top of the metro steps. “That mean anything to you?”

“A membrane?” the director echoes. “No. Why?”

“I think your nephew might be unwell,” Amir says, though he knows he’s not one to talk. He scuttles down the stairs to the southbound platform. “Any history of mental illness?”

“None that I know of.” The director’s concern sounds genuine. “I could ask his parents, but then I’d probably have to tell them about the theft, as well.”

“Hold off on all that. I’m on my way to him now.”

Amir ends the call just as the train comes screeching in. He puts his phone away and steps inside a compartment full of Grecian statues, a dozen white marble musculatures frozen in eerie poses. The silence is fucking terrifying. He finds an empty seat beside some naked philosopher and slumps down into it, then squeezes his eyes shut as they rattle off into the dark.

A transient snow is falling when he arrives at the Tannery District, which was becoming a bit of a tourist area until it flooded last year. Now it’s a mess, streets heaped with defeated sandbags and varied detritus. He passes a hulking sump pump gone silent, a solitary backhoe stretched all the way horizontal, grasping for something it’ll never reach.

As with Hatter’s Bridge, repairs are moving slowly. The majority of shops and eateries have moved on, leaving boarded-up husks behind—any of which would make a fine short-term hiding spot for a lad with a stolen head. Amir doesn’t want to sync the smartglasses again, for fear of tipping Lester off, so he starts checking the derelicts for signs of forced entry.

The pub with smashed windows and no door seems promising, but he only ends up startling a young couple mid-snog. In the adjoining alley he spots a little nest of insulated blankets, but the head poking out the top has silvery-grey hair, which corresponds neither to Lester nor to the mummified monk. He heads farther down the street, towards an abandoned billiards hall. When he sees a Crystal Palace logo spraybombed onto the brick facade, he knows he’s in business.

The door opens just wide enough for a skinny nineteen-year-old to slip through; Amir has to barge it with his shoulder until he can do the same. It’s dark inside, musty. The rotting wood floor feels almost like sponge underfoot. He cranks the little lamp on his phone, illuminating a gutted bar, a wire-stripped ceiling, a lonely herd of pool tables too warped to salvage.

“Lester?” he calls. “You in here, mate?” He moves slowly towards the bar, sweeping the shadows. “My name’s Amir Murtle. I’m a PI, here on your uncle’s request.”

There’s no answer, but he hears shuffling feet.

“I’m only here to retrieve the item,” Amir says. “Your uncle doesn’t want to lay charges. Just wants the head back where it belongs.”

He rounds the corner of the bar, boots crunching on broken glass, and sees there’s a back room with a single table. Something roughly ovoid is sitting on the ruined blue felt. Amir feels a gelid prickle up and down his spine as he gets closer. Mottled bog-brown skin, glistening in the phone light. Bared teeth. Imploded eyes.

The warped features are disturbingly familiar; Lester might have decapitated the very monk that was on display during Amir’s school trip three decades prior. Amir is so transfixed by the head that it takes him a moment to notice the thief. Lester is standing in the corner, facing it like a castigated child, wearing the windbreaker he had on in the security cam footage. He’s eerily still.

At times like these, Amir really wishes he could trust his own neurons.

“Has it been calling you, too, then?” Lester asks, in a croaky voice that’s barely done changing. He rubs one leg against the other, stork-like, and Amir sees he’s missing a sock. “It told you to come here?”

“The head?” Amir tries to make his voice kind. “No, mate. Like I said, your uncle hired me.” The grocery bag used to transport the monk is now rumpled up and stuffed into one of the billiard pockets; he grabs it out. “I’m going to just pop the monk back in here, then give your uncle a ring and tell him what’s what.”

“Calling’s not the right word, I suppose.” Lester’s hands are out of sight, and Amir has the sudden paranoia that he’s facing the corner because he’s pissing there, which would make it twice today someone has toilet-talked him. “Has it been showing you things?”

Amir’s stomach drops. “Things?”

“Things.”

“What things?” Amir persists, forgetting to sound kind.

“Things, Dag.” Lester huffs a laugh, tips his head back. “Corpses decomposing on the ceiling. Giant crab creatures in the canal with miniature cities on their backs. All those people walking around with extra spinal column coming out of them, stretching way up into the sky, but you can never quite see what it’s connected to.”

Amir stares down at the mummified head on the pool table. All the little hairs on the back of his neck spike up. “You’re saying the ghost of this dead monk is handing out hallucinations.”

“No!” Lester makes a familiar hacking noise; it must be genetic. “No. That’d be fucking—that’d be stupid.”

“Oh.” Amir feels only slightly relieved. He switches his gaze back to Lester, whose hallucinations are not quite the same as his, but certainly adjacent. “You want to turn around? Bit spooky, speaking to the back of you.”

“In a moment,” Lester says, sounding petulant. “I’m building up my nerve. You’re here to take the head, then. Not to help.”

“Help with what?” Amir asks.

“One’s not enough,” Lester says. “We have to go back for the others tonight. Get a critical mass. Don’t you agree?”

“You asking me, or the head?”

“Jesus. You don’t know anything, do you.” Lester’s voice is cracked. “I don’t know why it bothered calling you.”

He whirls around, and Amir was half expecting him to have sharp black beaks in his eyeholes, or smooth shit-spackled stone instead of a face, so it’s nice to see soulful eyes and a dusting of moustache in the millisecond before a swinging cosh collides with his skull.

Amir limps across Hatter’s Bridge, nearly home. The shambles has been disassembled and trucked off, and they’ve even contrived to get rid of the bloodstains, but he can still smell its greasy, coppery stench in the cold air. Or it might be coming from his smashed-in nose, which is leaking everywhere.

The director’s not answering, and since Amir has no one else to call he calls Bravetti. It rings and rings as he crosses the plaza, as he turns up his snowy street. There’s a brief intermission when he uses his phone to unlock the outer door. Then it keeps ringing, echoing through the concrete spiral shell of the staircase as he staggers up to his apartment.

She answers just as he turns the door handle. “Make it quick, mate. I’m following someone right now.”

Amir does not know where to start, so he starts angry. “You said this was an easy one,” he snaps. “I was just fucking pummeled.”

Bravetti gives a gasp of laughter. “No! What, by the wee nephew? The wee nephew pummeled you?”

“Had a billiard ball in a sock,” Amir says, shutting the door behind him and fumbling it locked. “Could’ve bloody killed me. I’m probably concussed.”

“He scummed you!” Bravetti yelps, then lowers her voice. “The cheek of it. Bet he’s never even seen the film.”

“Cracked me right in the face. Broke my nose.” Amir goes straight to the codeine and glugs down the last of it, tongues the dregs. “Then I’m down on the ground, shielding myself,” he says, discarding the bottle, hobbling to the freezer, “and the little fucker starts swinging for my knee instead. It’s swollen to hell already.”

“God. Did you get the head back, at least?”

“Of course I didn’t get the head back.” He glares at an empty ice tray, starts scraping frost off the bottom of the freezer. “He took it with him when he scarpered. He thinks—” Amir presses an insufficient palmful of ice shavings to his blood-tacked face. “He thinks it’s talking to him, or showing him visions, or something.”

Bravetti is silent for so long Amir has to check they aren’t disconnected. The codeine’s kicked in, dousing his pain receptors in warm syrup, and he sinks down onto the bed. When she finally speaks, she sounds cautious in the way he hates so badly, the way he never knew she could sound until a couple months ago.

“Maybe this isn’t a good job for you,” she says. “If the nephew’s off his nut, and talking to you about visions, it might make you—I dunno. It might make you relapse. Start having those episodes again.”

Amir checks the ceiling for decomposing corpses. “You don’t think it’s fucking odd that I was hired to track down someone with the same exact problem as me?”

Silence again. The lump of ice shavings has melted away. He grabs his lone dishcloth and starts sponging the softened blood from his philtrum.

“I was hired for it,” Bravetti says, calm and decisive again. “I gifted it to you, remember? And there’s loads of nutters in this city, so no. Not statistically.”

“Cheers.”

“I’m going to ungift it from you, though,” she says. “Soon as I get back in town. You need more time off. Maybe see the psychologist again.”

“I don’t want—”

“If nothing else,” Bravetti cuts in, “they may be able to help you sort out the trauma of getting your arse handed to you by an adolescent. Bye-bye.”

She ends the call, and Amir momentarily wants to pitch his phone at the wall. Instead he dials a more recently acquired number, sets it to speaker, and struggles up off the bed. He rattles open the barren utensil drawer. His best option is a steak knife.

“This the detective?” Fay’s voice comes accompanied by thudding club music. “How’s mortality going for you?”

“Hate it,” Amir says. “I’m going to need some painkillers and a fuckload of pep pills if you’ve got them.”

“I’ve got everything,” Fay says. “Big night tonight, eh?”

Amir sits back down on the edge of the bed, making it ripple. “Sure. Big night.”

“You find Lester, then?”

“Did.” He starts sawing through the edge of the cast, right between his thumb and forefinger, serrated metal teeth grinding fibreglass down to powder. It’s going to take a while. “Can you meet me on Hatter’s Bridge a half hour from now?” he asks. “With the stuff?”

“Think I can duck out, yeah. I’ll message you.” She pauses. “Is he okay?”

“He’s grand,” Amir says. “I’m a mess. But he’s grand. See you in a half hour.”

He redoubles his efforts with the steak knife, showering the bed with tiny splinters of fibreglass and wisps of padding. He sets his jaw, stares at the handgun on the rickety table across from him. No need to cleave the cast all the way off. He just has to free up his grip and his trigger finger.

St. Johan’s is impressive at night, a great stone beast lit from below by LED pits. The carved buttresses look like a reptile’s splayed legs. The stained-glass windows are eyes, nocturnal predator-yellow. It puts Our Lady of the Tar-Black Snow and her piddly angels to shame, every curve and cleft somehow both holy and menacing.

Fay’s amphetamines might have something to do with that, too. He’s been inhumanly focused for the past two hours, huddled in a cafe across the street from the cathedral’s back entrance while a well-sequestered pocket cam watches the main one. Lester has yet to show, even though Amir remembers the words clearly: One’s not enough. We have to go back for the others tonight.

Maybe Lester changed his mind, or is just fully out of it. But Amir doesn’t think so, and that is why he didn’t tell the client his nephew is returning to the scene of the crime. He needs to figure out what’s going on first.

The wikis he has his phone reading to him are no help, all persecuted religious order this and possible self-immurement that. As best he can tell, three soldier-monks got lost in the desert outside Damascus during the Third Crusade, came back raving, and enlisted a local stonemason to build them three sarcophagi that could be sealed from the inside.

Their order hushed it up to avoid going the way of the Templars, who’d been burned at the stake for heresy and inappropriate kissing, then several centuries later the sarcophagi were excavated and shipped to Glimshire, and several decades after that someone founded a semi-successful brewery called 3 Mad Monks—for other uses, see Three Mad Monks, disambiguation.

It’s not as interesting as Bravetti made it out to be, and doesn’t explain in the slightest why he and Lester have both been having hallucinations, possibly beginning around the same time. That’s why he needs to have a proper chat with the lad. At gunpoint, if necessary.

And there he is. Scurrying down the block, familiar grocery bag swinging from his fist. Amir cranes forward to watch as Lester hops up the steps. His uncle has not seen fit to take him off the employee register, so his phone unlocks the back door with no issue at all. He marches inside. The retrofitted metal door swings shut behind him and Amir thinks momentarily of self-immurement.

Then he gets up, sets his mug in the grey dish tub, slips out of the cafe.

Amir is not on the employee register, but he has a pneumatic door-jack that works just as well. The hinges give way with a groan and bone-crack. Amir shifts the door over, casts one look up and down the snowy street, and steps through.

He’s in the back offices of the cathedral, all cubed concrete and flickering fluorescents. It reminds him of his unfinished apartment block until he hits the sanctuary. For a moment the rows and rows of pews seem to be rolling towards him, a stone tide. He’s not sure if it’s from the pep pills or if the hallucinations are returning.

The stairwell is tucked into a corner with the ornate confessional booths; someone approached it recently enough to trigger the information holo and donation suggestion. Amir feels for the familiar grip in his pocket. He can hear movement below, but sees no light. The air around the stairwell is cooler. Wetter. Almost has a taste to it.

Down into the squid-ink dark. Amir keeps one hand on the velvet guide rope and one hand on his gun, tries to make his footfalls soundless. The catacomb is somehow deeper than he remembers from the school trip, even though his legs are longer now. Descending its hewn throat makes his skin go clammy and his heart pitter-patter. Bravetti would have a real laugh, but she might not be chemically capable of fear.

Light at last. The pale electric sort, from a phone torch, which is comforting down here where everything smells so ancient. The scene it illuminates—less comforting. The three famous sarcophagi are roped off, with a hastily hung closed for maintenance sign there for emphasis, but Lester has traversed that.

The central sarcophagus is open, its lid scything outward like a spread wing, and Lester is crouched inside like a succubus or incubus or whatever the hairy thing in that one painting is, straddling the corpse’s chest in order to more easily saw its head off. The original head is perched on the open lid, watching the proceedings through its collapsed eye sockets, and something the colour of old blood seems to be growing out of its earholes.

Amir takes the handgun from his pocket, not aimed, but obvious. “Lester,” he says. “Time to tell me what’s going on. And don’t say to look at the wikis. I hate history.”

Lester’s head jerks up. He sees the gun and his soulful dark eyes go wide. He sets the knife down slowly. “Don’t shoot,” he says. “Jesus Christ.” He blinks. “You know those who hate history are doomed to repeat it.”

Amir takes an angled step, to ensure a good sightline on both Lester and the disembodied head. “I know being clever is important to you,” he says. “But put that aside for a moment. Just explain the head, and the hallucinations, and what exactly you’re trying to do.”

Lester does the inhalation of one about to explain things to an idiot. “The Three Mad Monks didn’t lose their minds in the desert,” he says. “They found God. By which I mean the effectively immortal Precambrian parasite that had been dormant for millions of years and makes tardigrades look like pushovers.”

Amir recalls the last article on Lester’s wall.

“Recent geological activity had brought a spar of ancient rock towards the surface. The monks met it halfway, in the chasm where they were sheltering from the sandstorm.” Lester shifts slightly; the corpse beneath him makes a slimy, rasping sound. “The parasite revived and took three hosts. But it couldn’t really do much with them. The structures of the human brain are a long way from the Precambrian organisms it used to puppeteer. It’s smart, but not that smart. It managed to buy itself time to figure things out, though. Got the monks to pickle themselves.”

Amir looks at the head again, at the rust-red tissue blooming from its ears and nostrils like cauliflowers. He decides to delay judgement on whether it’s really happening or not. “How’d you find all this out?”

“Well, there’s the Aghast Missive,” Lester says. “Letter fragment from the bishop who wanted to make sure nobody found out about the monks’ seeming suicide. And there was a Scottish scientist named Hieronymus McLaverty, who did a forensic investigation of the bodies in the 1800s, found some odd things but died before publication. Lately, though, I’ve just been talking with the parasite.”

“Via hallucinations,” Amir says. “The prehistoric parasite in a dead monk’s brain is handing out hallucinations, which is somehow less stupid than a dead monk’s ghost doing it.”

Lester folds his bony arms. “The hallucinations were just static,” he says. “Now I can hear it much clearer. The best way is—may I show you?”

“Slowly,” Amir says.

Lester reaches, slowly, for the slick, withered head. He cradles it in both hands, presses his brow to its brow. In the pale glow of Lester’s phone torch, Amir sees the rust-red tissue flexing out from the monk’s nostrils knit itself into a sort of hook. It thrusts its way up Lester’s nose with no warning.

“Doesn’t hurt,” Lester says, before Amir can leap forward and rip the thing free. “This is the most direct way to commune with it.”

The eeriness is stacking up, so much so that Amir’s whole back is now drenched in cold sweat and his left knee, the one Lester smashed with a billiard ball, is trembling. His hands, thankfully, are good and steady.

“Right,” he says. “If you’re talking to it now, ask it what the fuck it wants.”

“I already know that,” Lester says. “It wants to remake the world in its image. Make it much more interesting.”

Amir thinks of sapient storm clouds and automated human sacrifice.

“But to do that, it needs a lot more hosts,” Lester continues. “And to reproduce, it needs a critical mass. That’s why we came back for the other slivers in the other bodies. To speed things up.”

“Are you being brain-controlled or something, then?” Amir asks. “How the monks were?”

“Not at all,” Lester says, sounding genuinely offended. “This is God.” He kisses the head’s shrivelled-back lips, then beams at it. His bright white teeth are smeared with rust-red spores. “And I’m its prophet.”

“Grand,” Amir says, forcing himself to ignore the inappropriate kissing because he’s come to the most crucial bit. “Now ask it what it wants with me. Ask it why I’m getting the hallucinations.”

Lester is silent for a moment, assumedly communing, then he gives his head a minute shake, making the knotted red stuff shiver. “It’s honestly not sure,” he says. “But it does think you’d be a good host. Your neural architecture is quite accommodating.”

Amir does not find that flattering, and he is considering how far he might be able to drop-kick the monk’s skull off Hatter’s Bridge when he hears a mechanical whirring. His teeth clench at the noise. Then a familiar silhouette comes lurching out of the dark, towering over Lester and the sarcophagus.

Same spiny flippers. Same goggly dead eyes. But it’s twice as big as last time, and the gleaming tusks look razor sharp.

The bones throb in Amir’s broken hand.

“Rematch,” the animatronic walrus says.

It’s a hallucination, of course. No hallucination in the history of hallucinations has ever more clearly been a hallucination. But Amir’s limbic system does not discriminate with a one-tonne nightmare machine barrelling at it, and he squeezes the trigger on reflex, three times, pyramid placement.

The electropellets bounce right off; for a nonsensical moment he wishes he’d brought actual bullets. Then he sucks down a deep breath, braces his feet, and opens his arms. He reminds himself that he is facing off against thin air, that a prehistoric parasite is tweaking his neurons. He’s going to let this bastard walrus pass right through him.

The impact slams him off his feet. His gun skitters across the catacomb floor and the back of his head collides with hard stone, smashing stars across his eyes. Beyond those dancing constellations he can see the walrus looming over him, see the blurry, manic grin. He hears a tinkling ringtone in his ears.

“Your mind makes it real, Neo,” Lester calls. “Or I suppose your central nervous system does.”

Amir rolls left as the walrus’s tusk descends. He comes upright with a new stratagem: evade the animatronic walrus, destroy the disembodied head. He spins towards the sarcophagus, where Lester is still sitting on Mad Monk Two’s chest, cradling Mad Monk One’s head. Beside him, resting on the open lid, is the big serrated stalking knife Amir made him set down.

They both lock eyes to it at the same instant; Amir lunges but Lester is much closer. He tucks the head under his armpit and grabs the knife handle, gives the air a warning slash like some kind of bloody pirate. Amir can’t stop—too much momentum, plus an animatronic walrus bearing down on him from behind, whirring in his ears.

He goes low, gets inside the blade, and his suspicion that Lester got lucky with the cosh but has no idea how to use a knife turns out to be correct. He wedges Lester’s elbow, twists hard. There’s a tendon pop, a wail, and the knife clatters to the floor. Amir snatches it up and turns just in time to parry a scything tusk.

“Death is a membrane,” the walrus says. “I will usher you through it.”

Amir does not banter with hallucinations, but he jabs for its blank eyes, and when it rears back he puts all his force behind the blade, driving it up into the moulded plastic belly of the beast. Slick black oil sprays outward, even though he is almost certain animatronics are not fuelled by such, and catches him full in the face. He howls, blinded, and the walrus laughs a creaky, phonograph laugh.

Then he’s pinned, the thing’s flippers crushing him to the floor, squeezing the wind from his lungs. He blinks his stinging eyes clear. Sees Lester squat down beside him, the monk’s head still tucked under his armpit. The red stuff is stretched thin now, suspended between dead and living nostrils like a strand of mozzarella, but as he watches, Lester delicately detaches his end and pushes it towards him instead.

“Here,” Lester says, as Amir feels a tickle at the rim of his nostril. “God wants to explain things a little better.”

Amir kicks. Writhes. The red stuff creeps inside his nose, claws softly up his septum, and he can already feel a thing on the edge of his consciousness, hovering over his shoulder. He sees a crop of techno-organic machines, yellowish scissor limbs growing out from dark soil. Long pale creatures wriggling across splendorous ruins. An empress with a weeping mask.

Then he sees the thing itself, an eyeless thing in a tailored suit, seated at a living, pulsating piano he knows is his own oh-so-accommodating neural architecture. It readies its hived and veiny fingers—

“Oi.” The cool, dry voice interrupts from a universe away. “He’s atheist, you wee creep.”

The thing inside Amir’s skull unhooks, tugs free; his eyes clear and he sees Lester has jerked upright, taking the dangling red corkscrew with him. He’s staring at the stairwell. So is the animatronic walrus. Amir cranes his neck to join the party, and sees that Bravetti has not only found him in his hour of need, but also found his fallen handgun.

“You got lethals in here, Amir?” she asks.

“No,” he croaks.

“Aren’t you a lucky little fucker,” she says to Lester, and shoots him.

There’s a thump and a sizzle and he topples sideways. The monk’s head spills from his spasming hands. That still leaves the walrus to deal with, but of course Bravetti strides up as if it’s not even there. It tracks her with its bulging eyes.

“Six missed calls, Amir,” she says, yanking his phone from his pocket and showing him the screen for proof. “Six. It’s very unprofessional of you.” Her voice is no longer cool and dry. “What in the hell’s going on?”

Amir gives an experimental shove, and discovers the walrus is now helium-light. It drifts towards the ceiling of the catacomb and sticks there like a baleful balloon. He gives it a two-finger salute, then shifts his attention to the monk’s head, which is still rolling across the floor, momentum sustained by tiny red ear- and nose-cilia.

“Just a moment,” he says. He grabs the stalking knife, crawls after the head, and grabs it by the ear. “You can see this, right? The red stuff?”

Bravetti frowns. “The living bogey? Yes, mate.”

Amir relishes that for a second, like a well-picked lock, then starts stabbing. The rust stuff wriggles back inside the cranium, seeking sanctuary, at which point he tears the lower jaw free, rotates the skull, and drags the parasite out through the new aperture. He dices it into pieces, then uses the knife handle to mash those pieces into slurry.

“It’s an ancient telepathic parasite,” he explains. “A discovery that revolutionises biology and evolutionary theory and all that. It’s been remotely fucking about with my brain for the past couple months, and I suppose with Lester’s, too.” He checks the ceiling; the walrus is gone, but he will take no chances. “We’ll have to do this to the other two monks as well.”

Bravetti gives a wise nod. “Always figured it was something like that,” she says. “There was this Scot who dissected one of them in 1811, see, and he went absolutely starkers.”

“Me too, for a bit.” He looks down at the mash. “But I think it should be over now. The episodes.”

Bravetti shrugs. “We should probably torch it all, just to be safe. It’s been an age since I set something on fire.”

They drag Lester up the stairwell and deposit him on a pew, then Amir stands watch while Bravetti syphons some petrol from a lorry outside, then they go back down into the catacomb and douse the remains of the Three Mad Monks. The searing smell of petrol in Amir’s nostrils is infinitely preferable to a spongy hook.

Bravetti lends him her lighter to do the honours, and they step back to watch the crackly blaze. It feels quite cathartic, and standing shoulder-to-shoulder with Bravetti, her jacketed arm pressed to his, feels good as well. He misses being able to lean over and say something stupid and kiss her.

“Maybe we should give it another go,” he says, before he can stop himself. “Now that the hallucinations are sorted. Maybe it’ll be different.”

She shakes her head. “You know it wasn’t about the episodes,” she says. “It was all the other stuff. Besides, you’re getting to like the new place, yeah?”

Amir thinks of his white prefab box, his gelbed and his rickety table, his one and only mug. “Yeah,” he says. “It’s good.”

They watch the heaped bodies shrivel and blacken, watch the spirals of greasy smoke rise. There will be no more school trips to see the Three Mad Monks, but it’s just as well, because thinking about kissing Bravetti, then thinking about the rust-coloured spores in Lester’s teeth, has ossified his rickety suspicions. He considers keeping it to himself, but Bravetti is already working her way there.

“Why you, though?” she says. “I mean, it makes sense it got to Lester. He was in close proximity.”

“The school trip,” Amir says. “When I was ten.” He exhales. “I snogged that head on a dare.”

“You what?”

“I snogged the mummified monk,” Amir says. “They had the one sarcophagus open, back then, and the teacher wasn’t looking.” He works his jaw. “I stuck my tongue fully in there. Everyone had to give me five quid.”

“Well.” Bravetti stares wistfully at the smouldering remains. “That’s one revenue stream closed off forever.” She frowns. “So, what, there are little bits of it in your brain? Little transponders that were picking up the static?”

“I should probably get scanned,” Amir admits. “Yeah.”

They wait until there’s nothing but char and bone, then smother it in foam from the church’s fire extinguisher and head upstairs. The electropellet stuck to Lester’s bony chest is nearly drained; he can twitch and slur now, and slurs mostly about God.

Amir fishes the lad’s phone out and dials emergency services, then taps out a brief anonymous message to Lester’s uncle. It’s the least he can do, since the head retrieval job is now totally botched and he has no intention of explaining himself only to end up facing arson or destruction of property charges.

He parts ways with Bravetti about a block from St. Johan’s, and a block after that he sees the red-and-blue strobe of an emergency vehicle, drone-escorted, hurtling towards the cathedral. Fay’s pep pills are long gone, and he feels awful. His right hand is puffed up and bruising again, which means he likely shifted some bone around. His broken nose is throbbing. His knee buckles every third step or so.

But at least it’s real, and when the snow starts to fall again it’s real snow, too, the big globby white flakes that stick and stay. He’ll still have to check in on Lester, of course. Steal the medical report and make sure whatever spongy rust-coloured spores got into the lad’s brain are not cancerous, or behaviour-altering, which would be bad news for the both of them.

He trudges towards home, breathing small packets of steam. The snow stops when he gets to Strand Street. The clouds slide apart overhead, leaking antiseptic moonlight over the plaza, over the public piano they’ve installed there.

Maybe when his hand heals up he’ll learn to play. The gleaming keys look inviting, and not at all like teeth.

“Headhunting” copyright © 2023 by Rich Larson

Art copyright © 2023 by Elijah Boor

Buy the Book

Headhunting

I love the story, I really do—it’s beautiful and compelling and evocative—but I started out with the fond hope that this might actually be a story where a person with intractable hallucinations just goes about their interesting life. This is not a story like that, and he is cured at the end, and the hallucinations are just something he gets to walk away from. So for that, I was a touch disappointed. Still, please keep writing—your writing holds the rich imaginings of brilliance.

This is just the sort of compulsively readable plot with bizarro worldbuilding that I’ve come to love in a Rich Larson story. I’d devour a novella set in this world.

I like the way that underneath the main story there’s hints of a strange, off-kilter alternative Britain that feels somehow a bit more Spanish than English.

This one of my favorite stories of all time– the humor and horror are perfectly balanced, and the solve at the end, along with the explanation of everything plaguing this detective is tight and amazing. The writing was compelling and smooth, and the story has a noir feel that poked fun at the gene while still managing to hit all the satisfying beats of a detective story. I had a really good time reading this.

I just wanted to point out, in case it’s a problem: When I was sharing this story via social media, [a different name] comes attached as visible meta-data instead of ‘Rich Larson”.

@@.-@ – Thank you for letting us know! The metadata you’re seeing is from our content management system, which lists the Tor.com employee who created (“authored”) the post on our site. The author of the story itself is Rich Larson–so glad you enjoyed it!

A great short read for a day when a lie down is necessary.

Mx. Larson, I love the way you describe ordinary things (a bit of water in a pan as a slice of water!) that conveys how these things look and feel, the way they reveal character.

I enjoyed the horror elements. It’s a compliment to you that I’m extremely grateful I finished my roasted tomato and mozzarella sandwich before I got to the red booger.

This was fun. I don’t think there’s a higher commendation I can give a short story, and I’ve read maybe thousands at this point.

Casefic is probably the genre I love the most, and this hits all my favorite notes. It stars a flawed protagonist with an unreliable point of view (not to be confused with an unreliable narrator– Amir is very honest with the reader about everything he’s doing and seeing, including the fact that he doesn’t trust his eyes one bit). For extra points it takes place in a cyberpunk future but leans more into classic noir than neon-noir, probably because the character is so grungy he just greases up my lens.

I remember on my first time reading it I was on the fence about whether or not I would be okay with there being a magical fix or explanation to Amir’s apparent mental illness, but by the end I was just so completely on board. Amir is such a reprobate, all the trouble he gets into feels inevitable. The conclusion to the story clicks into place with exactly the right beat. Some mysteries end with a forehead slapping “of course!”, but even upon my first read, I ended with a fond and exasperated eyeroll of an “of course“. Having gotten to know Amir, of course he’s exactly the kid that would have kissed a mummified head on a school trip dare.

The best casefic has an intriguing beginning, a logical progression to the mystery, and a satisfying end. This delivers it all with deliciously deranged darkness and a good dose of humor to chase it down.

It ranks so high on my list of favorite stories, I read it every few months.